The Guardian is one of the larger newspapers still running daily, owing in part to their large audience and web presence. They’ve been a publication since 1821, where they were founded as the Manchester Guardian, a British newspaper. Today, while they still publish a lot of content in the British sphere of influence, they are thoroughly a global paper, and even have a dedicated U.S. edition. In fact, they have four variations on their website; the U.S. Edition, the U.K. Edition, the Australia Edition, and the International Edition.

The Guardian covers a wide variety of topics. They have politics, world news, opinions, sports, tech, arts, lifestyle, fashion, business, travel, environmental issues, science, media, and even a dedicated crossword section.

Since The Guardian is nearly 200 years old, there is a lot of information out there about submitting content for publication with their organization. These days, a lot of it is old and out of date; one of the top Google search results is from 1999! Yet they have kept to the same information, more or less, so it’s still an up to date document.

The down side to all of this is that The Guardian has a very well-stocked list of contributors, which means it’s pretty difficult to get in. The most open section is the Opinion area, but it’s also the least valuable, though it’s really quite a matter of pennies on the dollar; The Guardian is huge enough that any link from any section is liable to be useful to you.

Understanding The Guardian

While The Guardian is a large international newspaper, they have a lot of rules, regulations, and processes in place for communicating with them and publishing on their platform. I recommend taking some time to read their Terms and Conditions / Freelance Charter. I’ll summarize the salient points here, though.

First of all, the terms and conditions are legally binding above and beyond any other contracts you make with the Guardian News and Media Group.

Each contribution is negotiated uniquely with the editor of the relevant section of the paper. Some may be paid, others may not. Negotiations include payment terms, as well as deadlines, expenses, and the rights acquired by The Guardian.

The Guardian guarantees quick response on rejections; if your pitch is rejected for a feature, you will hear back within two weeks. If it’s for a news item, you hear back within the day. Hearing nothing is a good sign, though you may have to directly ask the editor what the status of your pitch is if you don’t hear back right away.

If The Guardian accepts a pitch and negotiates a fee, but then does not use the feature, they will still pay for it, though they may reduce the rate for a spike fee.

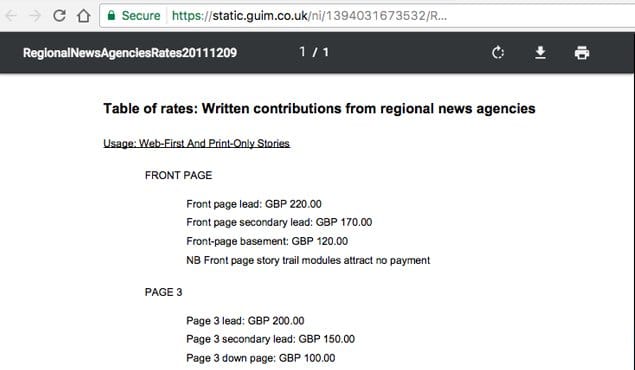

Different forms of content have different prices. The following are all in British Pounds: 310.68 per 1,000 words for commissioned contributions, 90 for a pick of the day, and a variety of rates for different regional news agencies. Note: these prices may change since the publication of this article.

All written submissions must adhere to the standard Guardian copyright terms.

Editors have a very low chance of accepting pitches from unsolicited freelancers. You’re welcome to try, but since The Guardian has a sizable stable of freelancers and on-staff contributors, they have plenty of content to cover most everything.

Additionally, you should avoid sending unsolicited pictures or artwork. The Guardian pays for such content, and thus is more likely to reject a pitch that includes them, as it would cost them more. Additionally, any physical media sent to their offices is not guaranteed to be used, paid for, or returned unless it is commissioned. They are not responsible for the loss of such media.

To sum up: The Guardian is very difficult to contact and get a pitch accepted, but is very valuable if you can swing it. They pay, often moderately well, with a 1,000-word post running nearly $400 USD, though currency exchange rates will apply and the value of the Pound has been dropping due to Brexit. Once you get a pitch accepted, you become one of their accepted freelancers, and will have an easier time getting future content accepted. Extremely successful freelancers may become regular contributors as well.

Step 1: Figure Out Which Section Best Fits Your Topic

The first step to getting a guest pitch accepted with The Guardian is to identify the right category for your topic. If you’re a marketer, you’ll probably want to skew towards something like tech or business. Sports are easy, though they are well covered already, and The Guardian has a special emphasis on soccer. News is generally very well covered, so if the only unique selling point to your pitch is that it’s newsworthy, you’re not going to be accepted. They like travel articles, they like specialized business topics, and their arts and lifestyle sections are flourishing.

One thing to remember is that The Guardian is a relatively centrist paper, with leanings towards the political left. This means conservative-leaning or outright alt-right opinion pieces will largely be rejected. Even if they were accepted and published, they would likely be lambasted by the readership of the site, and that can be devastating. What this generally means is that unless you’re a political blog in the first place, you’ll want to lean away from politics in your pitches. You should also avoid leaning the “wrong way” on certain issues the left cares about, like climate change, gun control, and diversity.

You can always aim for the general Opinion section, but I honestly consider it something of a last resort. It’s a little easier to get in, with lower editorial standards, but at the same time it’s the low-hanging fruit, meaning everyone is trying to pitch them and you have a ton of competition.

Regardless of what section you look to publish in, make sure the idea you have in mind is incredibly deep, complex, and insightful. They may be a newspaper, but they don’t want superficial content.

One footnote is that The Guardian is perhaps struggling a bit financially. More people than ever are reading it, but fewer people than ever are paying for it. With the proliferation of free media online, it’s increasingly hard for newspapers to stay in business. The Guardian asks for anyone who can to support or contribute to their finances. Now, there’s no implication or guarantee that a contribution will in any way help your pitch, but it certainly can’t hurt. It might be worth supporting them just in case someone decides to give you a second look because you’re flagged as a supporter.

Step 2: Identify the Accounts in Control of That Section

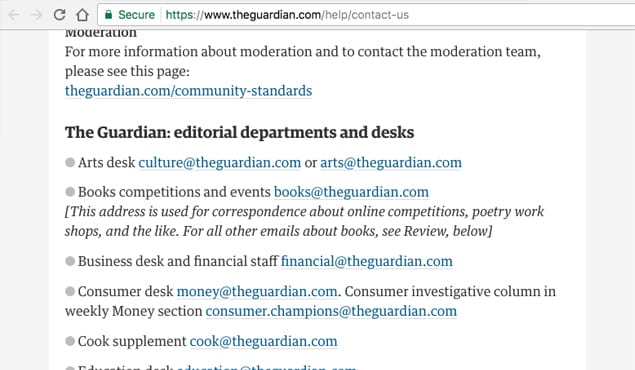

This is one area where The Guardian is one of the nicest publications on the internet. They actually publish a list of ways to contact them. Freelance pitches should always be submitted electronically; if you send something physical to one of their offices, chances are it will simply be shredded.

There are three ways you can contact someone at The Guardian.

The first method of contact is through one of their editorial department desks. Each section of the paper has a head editor and a general email address for contacting them. For example, the education section is [email protected]. The film desk is film@, law is law.editors@, money is money@, and so on. You can see the complete list on this page. For the most part, they are exactly what you would expect, but a few are goofy. For example, the environment section has no email listed, but prefers that you contact them via @guardianco on Twitter. The letters section is [email protected] rather than just letters@.

The problem with this method is that they’re such broad, general editorial desks that you’re not going to get much attention. You can try them as a last resort, but I prefer methods 2 and 3 instead.

The second method is to contact the editor of a given section directly. Unlike the department email addresses, The Guardian standardizes their staff email addresses. They are all the [email protected] format. So, for example, if you want to contact the lead tech editor for the west coast office, Merope Mills, you would send a message to [email protected]. Any time you can identify the name of an editor or lead reporter and want to send them a message, this is one way to do it. You can also search for articles that contain the staff list, like this one, which lists each team, their roles, their email addresses, and their Twitter handles. Just make sure to double-check that the person in question is part of the team, if the article is old.

The third method is to use the SecureDrop system. As a large international newspaper, The Guardian often deals with sensitive data. They may accept data from people who want to remain anonymous, or people who are whistleblowing and need protection, or people who may be under surveillance. You can find this system here. You will need to choose confidential – anonymous publications work against your guest post purposes – and choose words. Follow the instructions they provide.

Generally, method two is the best, method three is a backup, and method one is the last resort, unless you have a specific contact in The Guardian staff. If you have a specific contact, talk to them directly and ask them how they would like you to proceed.

Step 3: Develop a Compelling Guest Post Pitch

The guest post pitch should be short. Typically editors aren’t going to read more than 2-3 paragraphs before they reject a pitch, so you need to convey all the information you want to convey in that space. If your pitch is too long, prune it down.

What should your pitch contain? Start with a summary of what the post you want to write is. Generally, The Guardian publishes content with a news hook. I don’t mean news directly, but rather ways the news impacts your industry. To take a broadly covered example, they won’t accept a post about Brexit, what Brexit is, or how Brexit works. However, they might accept something from a tech person telling them how Brexit will affect tech companies in London, or what Brexit will impact with regards to Chinese imports. Specific topics are essential.

Next, you need to explain who you are and why you’re the right person to write this post. Anyone can research and write something about Brexit in general, but you might be uniquely qualified to write about British outsourcing and the projected impact of Brexit on the industry. Always play to your strengths.

Finally and most importantly, your email needs a unique and compelling subject line. Anything generic will be filed away with the 10,000 other generic pitches they received that week.

Step 4: Pitch the Editor or Contact for Your Chosen Section

Once you have a pitch, write it up and send it to your contact. They recommend only sending 1-2 ideas at most, so don’t give a dozen options to let the editor pick. Be focused.

Likewise, don’t send pre-written pieces. They very rarely publish these, due to liability and because it doesn’t give the editor room to customize the pitch. The editor, if they like your pitch, will give you specific instructions on the focus or sub-focus of the piece, the length they prefer, any media they want to commission, and so forth. Being open to conversation is essential.

Step 5: Create, Submit, Revise, and Publish Your Post

Finally, well, do all the work. Obviously, I’ve covered this topic extensively elsewhere on the blog. There’s nothing unique to say about The Guardian here; just read their content, talk with the editor, and figure out what works. Once you get a contact and a back-and-forth with an editor, they’re quite lenient with working with you to get something they want to publish. Don’t be afraid to take your time, shift your objective, and edit your post to make it work for their needs. Above all, be persistent. Writing for The Guardian is possible, but not easy.

ContentPowered.com

ContentPowered.com

Fatama Zohora

says:Hi, nice post. I have question though- I live in south east Asia, Can I pitch for guest post idea? as i did not see payments methods that could be used to pay someone outside of US, UK or Australia.